I’m sitting in our integrated arts studio/workspace at 9:00 am on a sunny Wednesday morning in May. Students all around me are measuring, cutting, painting, gluing, drilling, and re-measuring.

“Where can I get some white paint?” a student asks.

“Do we have a bigger dowel rod?” asks another.

“We’re out of glue sticks” another complains.

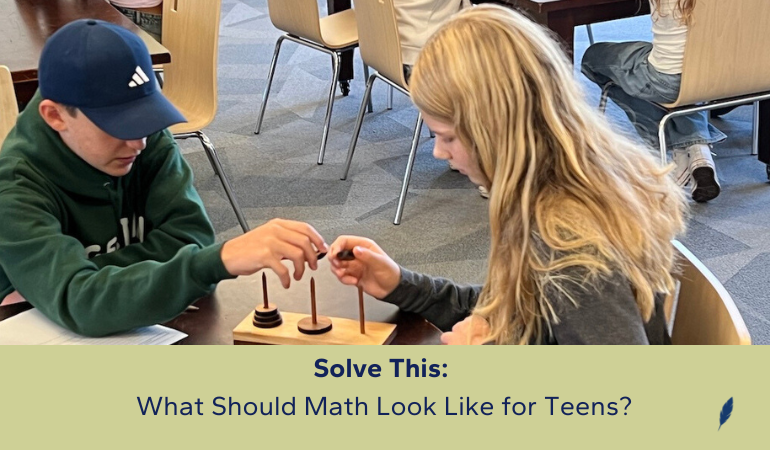

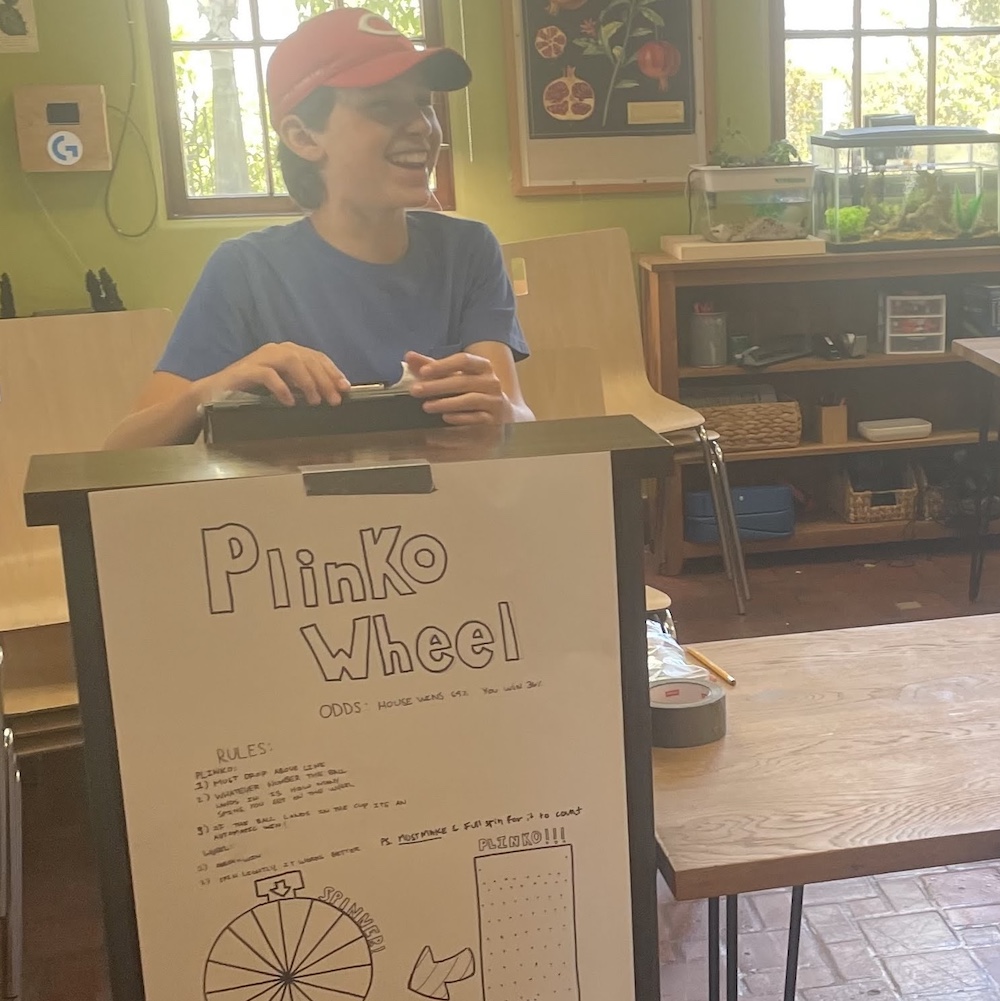

Students are working with Dixie cups, cardboard, X-acto knives, hot glue guns, cordless drills, plywood, and even 4×6 posts of lumber. They are building probability games to challenge one another (and their teachers) for our Math Fair. One pair of boys is outside, getting assistance cutting a door into their massive balloon-dart structure.

The Problems with Traditional Math

It still surprises me that this is a junior high math class.

Perhaps your memory of junior high math class is similar to mine:

- Desks neatly arranged in rows and columns.

- Students, grouped by age and ability, sitting in alphabetical order.

- 50-minute periods, five days per week.

- Teacher at the chalkboard or on an overhead projector.

- Ten minutes to go over last night’s homework (maybe even 15 if there were questions on the problems).

- Another fifteen minutes of notes and examples on the new lesson.

- And the remainder of class time to work on the assignment.

My teacher, Mr. Falstead, even looked the part — glasses, bald head, slacks, and a short-sleeved button-down shirt. Grades were based on homework, quizzes, and tests, all summarized into one neat little percentage.

Did this environment inspire engagement and curiosity for mathematics? Not for me. Nor my classmates, if memory serves. That didn’t happen until college when I started taking math education courses and realized math classes could engage, excite, and inspire – if only we value those outcomes.

Learning algebra (and higher math generally) can feel as inevitable, and perhaps as dreaded, as death and taxes. Recalling your own experiences, you may wonder: How will my child endure this crucible? Will they be Okay? Or will this experience crush their spirits?

Historically, it’s almost been too much to ask whether a child will come through the experience liking math even more.

Yet, love and appreciation for mathematics is precisely our goal at Marin Montessori’s Junior High. Our approach is designed not only to develop advanced problem-solving skills and logical reasoning, but to nurture confidence, resilience, independence, and a practical appreciation for the beauty and usefulness of mathematics.

Why Teens Need a New Approach

Adolescents are, by and large, disorganized. They’re tired. They’re emotional. They’re confused. But they’re also creative and passionate. They take risks.

Their brains are undergoing massive reorganization as they gain social awareness, and so they start wondering “Who am I? How do I fit in? How am I valuable to this group of people?”

There is an urgency for belonging. Look around any junior high or middle school, and you will see adolescents moving in packs. Visit Washington, D.C. in the springtime, and you will see them walking up and down the Mall in mobs (and forgive them for not making space – their attention is wholly on one another – not anyone else trying to walk along the Mall).

This desire to be together can lead some observers to believe that adolescents are just not interested in academic work. And there’s some sense to that.

Compare them to their elementary selves. Those kids were deeply curious about the world around them and were passionate about big work. They loved school for the learning. They were emotionally balanced and had healthy respect and admiration for the adults in their lives. Adolescents are all over the place.

Yet, to conclude adolescents have no interest in academics is a misunderstanding of their real needs. They occupy a strange place in human development. They are no longer children (and definitely do not want to be treated as such), but they are also not quite adults.

They want to understand and find their place in the adult world, but they need to learn alongside adults and feel valued for their contributions. They need to take risks and need to find creative outlets. They need to work together.

This is what makes the traditional math classroom so stifling. Not only do they miss a critical opportunity to connect math to the adult world through projects and applications and inspire continued interest and engagement, but they also can crush the spirits of the students for whom the traditional model is not successful.

Maybe the worst part of all is that this mismatch between their development and the system that is supposed to nurture it can send the message that some people are “math people” and some people are not. The all-too-common result: students who dislike math at an age from which it is difficult to recover.

Our Solution for Smarter Math

It is clear that we need to meet adolescents where they are – and not where we would like them to be. At the Marin Montessori School Junior High, we’ve come up with three unique solutions for meeting students’ needs in the math classroom.

The first solution is mixed-age and mixed-ability classes. This approach to math may sound unconventional, but it’s actually rooted in research and aligned with adolescent development. Instead of grouping students strictly by age or ability, we create mixed-age and mixed-ability classes that reflect how young people naturally learn and grow.

By working alongside peers of different ages, students have opportunities to both seek and offer help, which not only strengthens their understanding but builds a supportive, collaborative community. In this environment, students can develop confidence at their own pace without feeling pressured to keep up or slow down for others.

If teens are naturally social, we can allow them to be social, and we can do it in such a way that supports their learning, rather than hinder it. Mixed-age and mixed-ability groupings remove the induced hierarchy of tracking students that sends the unintended, but not-so-subtle message that “These students are good at math, and these students are not.”

Instead, students are in classes with older and/or younger students, and will naturally ask for help, as well as jump in and offer support. The innate desire for comparison fades away when students’ age and ability are intentionally mixed, and the desire for understanding may shine through.

As a corollary to mixed-age and ability classes, we have two adults in the classroom at all times, supporting student learning. Units of study are the same for all students (for example, data science), but we have the freedom to offer “whole class” instruction (say, on qualitative vs. quantitative data), as well as smaller “opt-in” instruction (perhaps a group of students want to learn about standard deviation, while another would like a review on measures of central tendency).

Students have the independence to choose which lesson best suits their needs, and the responsibility to attend the lesson and work through the exercises. This model also provides two perspectives on student learning, and two resources for student support when the need for one-on-one instruction is required.

The second solution is to individualize homework assignments. This is another profound departure from our own experiences as math students, and yet we’ve seen that the practice makes homework more relevant and healthier. Instead of everyone completing the same set of practice problems on a given evening, students are working through practice problems at their own particular level of difficulty.

This allows confident and motivated students to keep seeking greater challenges, as opposed to feeling bored and “checked out” with material they’ve already mastered. It also allows less-confident students to take their time with foundational skills and concepts.

Structuring homework in this way also removes the anxiety of comparisons between classmates and allows everyone to develop the necessary confidence and mastery to move forward with excitement for the next challenge.

The third solution is a decreased emphasis on quizzes and tests, and an increased emphasis on applied mathematics via student projects. How many of us recall thinking in math class, as an adolescent ourselves, “When will I ever need to know this?” Applied mathematics projects answer those questions, as well as give students the opportunity to (again) work together, be creative, use hands-on materials, and express themselves in novel ways.

Just last year, our students completed projects on:

- Data science, by polling their classmates using statistical questions, compiling the results,

- displaying them, and writing a summary statement of their findings.

- Solving equations and inequalities by creating a “How-to” booklet, comparing and contrasting the necessary steps.

- Using scale factors to draw and illustrate an image either larger or smaller than the original.

- Planning a city layout using linear equations and properties of parallel and perpendicular lines.

- Finding parabolas in the real world, taking photos, superimposing them on the coordinate plane, and deriving the quadratic equation.

- Creating probability games for our first ever “Math Fair” and inviting teachers and classmates to play.

Within each of these projects, there are requirements for all students, as well as opportunities for extension to demonstrate deeper understanding.

I am probably most impressed by the number of students who opt into the extension opportunities. It demonstrates an intrinsic desire to understand more challenging mathematics, which is precisely the kind of attitude we want to cultivate in our students.

Confident Kids, Ready to Excel

In addition to teaching math classes, I get to help the admissions office, particularly with alumni outreach. This means I keep in touch with many of our alums and get to see them at Open Houses, among other events.

When asked about the transition to high school, the near-universal refrain is that it is easy. Comfortable. Alumni speak directly about the positive impact of the applied mathematics projects they completed, and how confident they feel in their high school classes.

Alumni parents praise the “real world” applications that stretch across branches of mathematics and more accurately model the projects and challenges adults face every day.

When we talk with local high schools, we consistently hear how well-prepared Marin Montessori graduates are—not only academically but also in their sense of responsibility and independence. They enter high school ready to take on new challenges and advocate for themselves.

In our math program, we don’t just focus on equations and formulas; we cultivate critical thinking, self-direction, and confidence. Whether your child already loves math or finds it daunting, they’ll leave our program knowing they are capable and prepared to thrive in any academic setting.

Seth has been teaching teens and adolescents since 2005 and brings a wealth of experience to Marin Montessori School. Besides teaching in both public and private schools, he has taught at-risk youth at an alternative learning center, international students at an IB World School, and Japanese students through the JET Program. The Montessori adolescent environment is his favorite place to work with young scholars. Born and raised in Minnesota, he graduated from St. Olaf College with a degree in mathematics education. He also completed two years of graduate-level work through the University of Minnesota. In his free time, he enjoys just about any kind of exercise but especially cycling. And he is a huge fan of all Minnesota sports teams.